VERTICAL FEDERALISM (often simply called “federalism”) refers to the distribution of power between the national government and state governments.

Federalism has evolved as a result of various historical events, such as war and economic crisis; prevailing ideas, values, and beliefs; and government actions shaping the relative distribution of power between national and state governments. Overall, this evolution can be summed up in one sentence: “There have been ebbs and flows in relative power between the federal government and state governments, with the national government eventually gaining ground.”

Struggle Between National & State Power, 1790s – 1860s

Under the Articles of Confederation, states possessed almost all governing authority, and the federal government had very little power. It should come as no surprise, then, that immediately following the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, states continued to exercise significant government authority. States did this through NULLIFICATION; in other words, if a state deemed a federal law unconstitutional, it would nullify that law within its borders. This may seem a little odd because it counters the supremacy clause; however, when taken in a historical context, it is understandable why states acted this way. Nullification was so rampant in the years following the ratification, causing tensions to rise between states and the federal government — one such example of these tensions is the Nullification Crisis during the early 1830s, when President Andrew Jackson threatened to use military force to ensure South Carolina complied with federal tariffs laws.

The federal government was eventually supported in its efforts to exercise its constitutionally authorized powers by the Supreme Court under the leadership of Chief Justice Marshall through cases such as MCCULLOCH V. MARYLAND and GIBBONS V. OGDEN. McCulloch v. Maryland is regarded as the U.S. Supreme Court case that established the DOCTRINE OF IMPLIED POWERS (rooted in the elastic clause of the U.S. Constitution) and the DOCTRINE OF NATIONAL SUPREMACY (rooted in the supremacy clause of the U.S. Constitution). In Gibbons v. Ogden, the Supreme Court legally defined “commerce” as “commercial intercourse among states”, thereby expanding the applicability of the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause to new areas previously viewed as not falling under the umbrella of federal authority. Gibbons v. Ogden also reinforced the doctrine of national supremacy established in McCulloch v. Maryland.

Over time, the relative power of the federal government and state governments began to shift as the federal government (including Congress and the judiciary) shifted from the doctrine of nullification to one of PREEMPTION, in which state laws that conflicted with federal laws were invalidated.

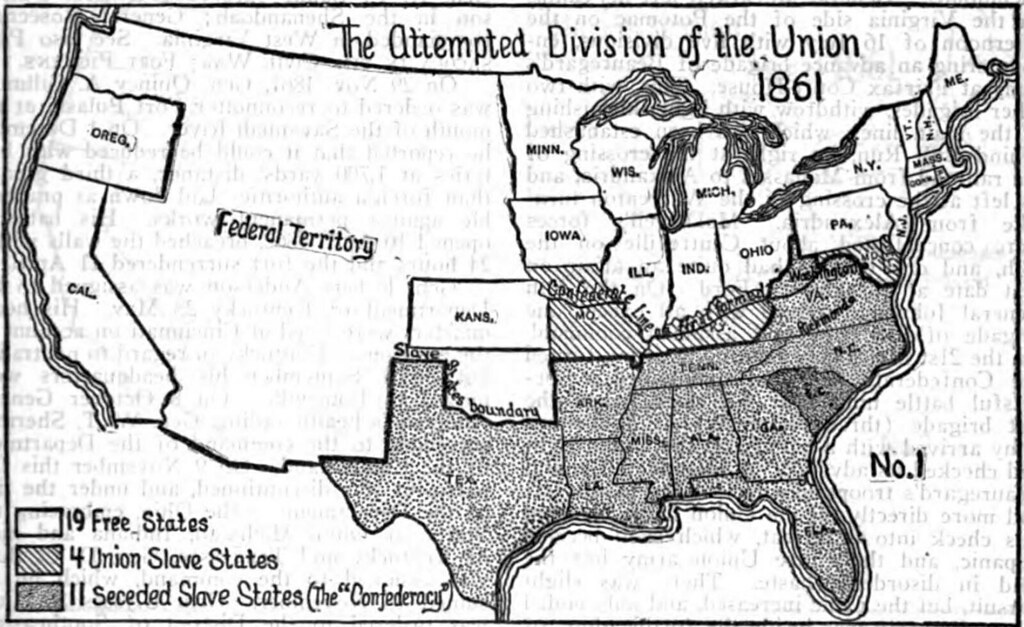

Civil War & Expansion of National Power

During the Civil War, the power of the federal government expanded significantly.

“If there was any constitutional issue resolved by the Civil War, it was that there is no right to secede.” – Antonin Scalia

The Union victory in the Civil War resulted in the decisive establishment of an indissoluble union. This was reinforced in TEXAS V. WHITE (1869), in which the Supreme Court ruled that “individual states could not unilaterally secede from the Union and that the acts of the insurgent Texas legislature–even if ratified by a majority of Texans–were ‘absolutely null'” (Oyez: Texas v. White). Maintaining an indissoluble union, in turn, required that the national government take steps to maintain this indissoluble union.

States that formerly seceded from the United States and joined the Confederate States were required to ratify the CIVIL WAR AMENDMENTS (also referred to as the Reconstruction Amendments) upon re-entering the United States:

- 13th Amendment: abolition of slavery

- 14th Amendment: due process; privileges and immunities; equal protection (we’ll discuss this one in more depth when we delve into civil rights and civil liberties)

- 15th Amendment: suffrage (voting rights) for African American

These amendments were viewed as radical expansions of federal power.

The presidency was vastly expanded as a result of the Civil War due largely to Lincoln’s interpretation of Article II of the U.S. Constitution, rooted in his belief that the president could exercise emergency powers not explicitly stated in the U.S. Constitution during times of war.

“I conceive that I may in an emergency do things on military grounds which cannot be done constitutionally by Congress.” – Abraham Lincoln

Dual (“Layer Cake”) Federalism, 1870s – 1930s

DUAL FEDERALISM, or “layer cake” federalism, refers to the institutional arrangement in which national and state governments are responsible for separate policy areas. Each level of government operates within its own area and layer, much like the layers of a cake. Under this system, the national government handles issues like foreign policy and national defense, while state governments manage areas such as education and public safety, with minimal overlap or collaboration between the two.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Supreme Court played an integral role in the emergence of dual federalism by supporting the doctrine of preemption when state governments acted in ways that fell beyond the scope of their constitutional authority. The Supreme Court’s role in promoting dual federalism is well illustrated in LOCHNER V. NEW YORK.

Starting in the 1870s, the U.S. entered the GILDED AGE, which was characterized in part by rapid industrialization and economic development. This was also the period during which we saw the rise of industrial titans such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, who amassed enormous wealth through industries like steel and oil, and the birth of philanthropy as these figures used their fortunes to fund libraries, universities, and other public institutions, promoting the idea of the “Gospel of Wealth.” The overarching economic philosophy at this point (and continuing until the Great Depression at the end of the 1920s) was LAISSEZ-FAIRE CAPITALISM, or “free market” capitalism, in which the market determines production, distribution, and price decisions and property is privately owned. As such, there was relatively little support for government policies that regulated the market sector, particularly if those regulations involved workplace conditions. This overarching economic philosophy was reflected in the Lochner v. New York decision.

Cooperative “Marble Cake” Federalism, 1930s – present

COOPERATIVE FEDERALISM, or “marble cake” federalism, refers to the institutional arrangement in which national and state governments share responsibilities for most domestic policy areas. Authority is blended between national and state governments, much like the swirls of a marble cake. Under this system, national and state governments collaborate on issues such as transportation, healthcare, and education, with overlapping roles and joint funding initiatives often blurring the lines between their respective powers.

Cooperative federalism initially emerged following the Great Depression as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s NEW DEAL, which expanded the role of the federal government in areas that were traditionally considered to fall under the reserved powers exercised by states relating to the “Three R’s”: relief for the unemployed and poor, recovery of the economy, and reform of the financial system. Almost all of these programs represented expansions in federal authority and involvement of the federal government in areas traditionally viewed as falling under the reserved powers of the states. For this reason, many of these policies were initially struck down by the Supreme Court, prompting the discussion of expanding the size of the Supreme Court and resulting in concerns relating to COURT PACKING. Furthermore, many of the New Deal programs focused on relief, such as Work Pays America, required cooperation between the federal government, which established and helped fund these programs, and state governments, which were charged with implementing the programs.

At this same time, the prevailing economic philosophy shifted from laissez-faire/free-market capitalism to REGULATED CAPITALISM, which maintains a capitalist economy with freedom from government intervention but allows government intervention to regulate the economy, guarantee individual rights, and provide procedural guarantees (around the same time, Lochner v. New York was overturned). This change in economic philosophy drew heavily on KEYNESIAN ECONOMICS and reflected an expansion of the federal government’s role in the economy.

As tends to be the case with war, WWII resulted in the expansion of the federal government’s role in various policy areas (particularly that of the executive branch). In the post-war period, the expansion of the federal government’s role in policy areas continued with the passage of the CIVIL RIGHTS ACT and VOTING RIGHTS ACT and Lyndon B. Johnson’s GREAT SOCIETY, which resulted in the creation of numerous social welfare programs including Medicaid, HUD housing programs, the Pell Grant, and HeadStart (and, similar to some of the New Deal programs, many of these programs require(d) cooperation and/or funding from both the federal government and state governments).

This general trend of expanding federal authority continued into the 1970s largely due to the advent of the REGULATORY REVOLUTION, during which the federal government took a more active role in regulating commerce and several social, political, and commercial activities (in fact, most of our regulations today stem from the regulatory revolution).

Shifts in Relative Power within the Era of Cooperative Federalism

The 1900s marked an era of unprecedented expansion in the size and authority of the federal government. To suggest that this is the only trend over the past century, however, is inaccurate.

As a result of the growing state share of public spending and public employees and increasing national deficits, the concept of NEW FEDERALISM took root in the early 1970s and continued through the 1990s. New federalism is based on DEVOLUTION, in which powers from the central government are delegated to the subnational government. New federalism had three main goals: (1) enhance administrative efficiency; (2) reduce overall spending; and (3) improve outcomes.

Several major actors in the federal government supported the concept of new federalism. President Nixon and President Reagan encouraged state autonomy and discretion by utilizing general revenue sharing, which gives states federal monies without telling them how to spend that money. The Supreme Court under Chief Justice Rehnquist issued numerous decisions supporting states in the exercise of their reserved powers. During the 1990s, President Clinton and his administration (democratic party) and the 104th Congress (during which both the U.S. House and U.S. Senate were controlled by the Republican party) worked on bipartisan reforms designed to “REINVENT GOVERNMENT“, expanding bureaucratic discretion and allowing states more flexibility and power when it came to domestic policy areas, including the implementation of certain federal programs.

This trend towards new federalism was reversed, however, following 9/11 and the WAR ON TERROR. These events helped refocus public attention on the national government and resulted in the expansion of the role of the federal government as a result of the creation of the Department of Homeland Security and other executive agencies such as the Transportation Security Administration (before 9/11, states were responsible for the security of their airports – there was no federal agency charged with this function), and the passage of laws such as the PATRIOT ACT.

Today, the struggle between national and state power continues. For this reason, many have stated that we are currently witnessing COMPETITIVE FEDERALISM, in which states and the national government seek to redefine their roles in key policy issues. Some issues where we have seen this redefinition of roles occur include:

- Immigration: Immigration has traditionally fallen under the authority of the federal government; however, states and local governments have started enacting laws regarding immigration, including Arizona’s “show me your papers” law and sanctuary city laws and ordinances.

- Legalization of marijuana: The federal government has classified marijuana as an illegal substance; however, many states have legalized marijuana for medicinal and/or recreational use.

- Abortion: Abortion laws fell almost exclusively within the realm of state authority until the Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade. From 1973 until 2022, states have continued to play a role in abortion policy by setting restrictions, which is permissible under the framework created by the federal government in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood vs. Casey so long as state laws and regulations do not have the impact of overturning Roe v. Wade de facto (i.e., in fact as opposed to in law). In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Supreme Court held that the Constitution of the United States does not confer a right to abortion, overturning Roe v. Wade and returning abortion policy to the states.